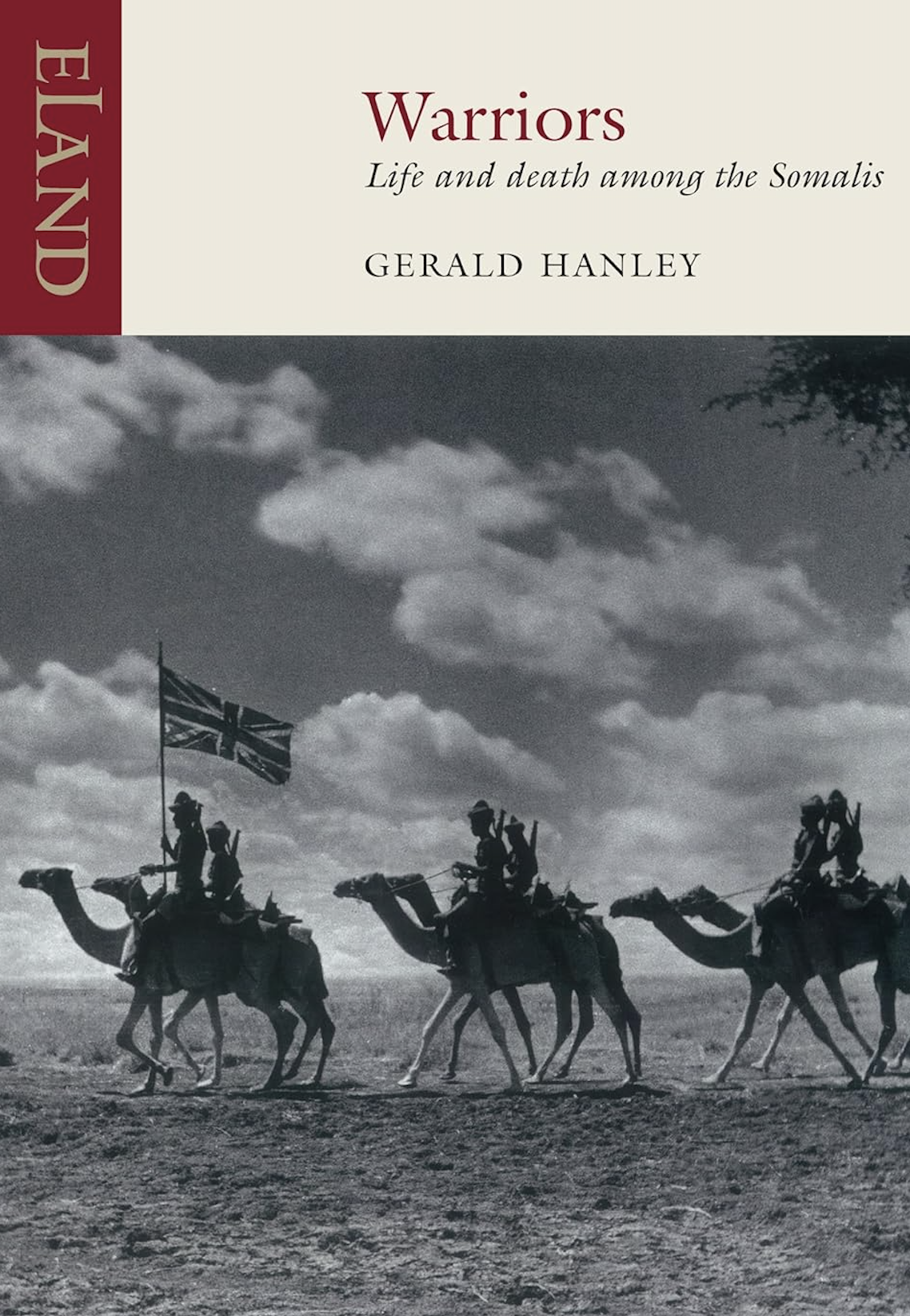

Book Review—Warriors: Life And Death Among The Somalis—Part 1

January 16, 2026

If you take a stroll through the alleys of your hometown, and study the faces around you, you might notice something uncanny. Despite their varied facial expressions and features, they carry echoes of your own being. In other words, they are not so different from you; each face, in some ways, is a reflection; an alternate self behind a different mask. This is the nature of society: a grand contagion of ideas, gestures, and unspoken codes. In fact, it was Sigmund Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents, who observed that cultural influence operates as a kind of pressure, shaping not only the self but entire civilizations.

Through this lens, one might approach Gerald Hanley’s Warriors: Life and Death Among the Somalis, not merely as an isolated memoir of a British colonial officer in the Horn of Africa, but as a text ingrained in the intellectual and cultural currents of its time.

Gerald Hanley (1916–1992) was an Irish writer and a British colonial officer known for his vivid portrayals of life in Africa and Asia. Born in Dublin, he served in the British army during World War II, spending time in British Somaliland, Burma, and India, and those experiences deeply influenced his writing. Hanley’s most notable work, Warriors: Life and Death Among the Somalis (1971), is based on his time as an officer in Somalia during the war. His descriptions of the Somali people and landscape are often stark and unsentimental, reflecting both admiration and the biases of a colonial administrator.

Beyond Warriors, Hanley wrote several novels, including Warriors and Strangers (1971) and Drinkers of Darkness (1955), which explore themes of isolation, colonialism, and human endurance. His work, though less widely read today, remains an important part of the literature on British imperial encounters of the 20th century.

Hanley’s Warriors: Life and Death Among the Somalis, is, at first glance, a work of stark realism: a straightforward account of a British officer stationed in Somalia during World War II. His prose is unsentimental; his observations unsparing. He describes the land as merciless, the people as fiercely independent, shaped by austere conditions and an environment that tolerates neither weakness nor sentimentality. Yet, beneath the surface of this rugged memoir lies an older, familiar narrative: the colonial writer as both the observer and outsider, drawn to the very people he claims to find mysterious, often intimating that something is wrong with them.

Hanley is neither the first nor the last European to wrestle with the paradox of admiration and alienation. Like T.E. Lawrence in Arabia or Richard Burton on the East African coast, he seems caught between awe and exasperation, between a deep respect for Somali resilience and the colonial instinct to render them unknowable. He marvels at their fearlessness, their fatalism, their unwillingness to be governed by foreign powers, yet his admiration is laced with the same exasperation that has colored many European accounts of Somali society.

Anyone with nuanced knowledge of literature knows that Gerald Hanley is not only writing the record of his life in “the isolation of wastes” and “its barbaric savages,” as he calls it frequently, but also echoing the scripts of old colonial writings.

In Warriors: Life and Death Among the Somalis, Gerald Hanley, much like Shakespeare in The Tempest and Conrad in Heart of Darkness, constructs the native as an enigmatic, often resistant figure, at once admired and alienated, fierce and unknowable. Across these three works, colonial encounters are mediated through the European gaze, shaping how indigenous people are understood and depicted. While each text presents moments of recognition and begrudging respect, they also reveal the underlying tensions of imperial thought: the native is not only different but exists in a realm of obscurity, of unfathomable, forever outside the full grasp of the European observer. And it is this substratum we will be discussing in this piece.

Across these three texts, we will examine the indigenous figures from Hanley’s Somalis, Shakespeare’s Caliban, to Conrad’s Africans, and how they are framed through a duality that both romanticizes and vilifies them.

Hanley’s Somalis are portrayed as an almost elemental force: unyielding, indifferent to death, and bound by a fatalism that Hanley sees as both admirable and frustrating. He describes them as a people that “cannot be ruled,” a sentiment eerily reminiscent of how Prospero speaks of Caliban’s resistance or how Marlow’s colonial peers view the Africans.

Caliban, Shakespeare’s archetypal “savage,” embodies the same contradiction. He is simultaneously brutish and intelligent, capable of eloquence yet dismissed as a beast. Prospero’s words— “A devil, a born devil, on whose nature/Nurture can never stick” (Act 4, Scene 1) capture the colonial impulse to both recognize the native’s potential and deny him full humanity. Hanley’s Somalis are framed in a similar way: resilient and proud, yet ultimately “fated” to a way of life that precludes civilization.

Conrad’s Natives, particularly in Heart of Darkness, are reduced to shadows, voices, and gestures—figures of elemental existence rather than individuals. They are often depicted as moving in “ritualistic” patterns, embodying the mystery and unknowability that colonial writing often ascribes to native populations. Hanley, too, describes Somalis in terms that suggest an almost mythic quality—untouched by the modern world, governed by an unshakable sense of destiny.

One of the striking similarities between Warriors, The Tempest, and Heart of Darkness is the way native resistance is framed not as a rational, political response to oppression, but as something instinctual, almost primal. Hanley’s Somalis do not simply resist foreign rule; they are portrayed as inherently ungovernable.

He expresses admiration for their unwillingness to be ruled, yet this refusal is presented less as a conscious rejection of colonialism and more of a fundamental, almost unconscious trait of their character. Caliban’s defiance follows the same logic. When he tells Prospero, “This island’s mine, by Sycorax my mother” (Act 1, Scene 2), his claim is dismissed as the irrational adamancy of a creature incapable of governance. His rebellion is not seen as political assertion but as an inherent inability to submit to order. Through the same light, in Heart of Darkness, native resistance—whether through silence, retreat into the jungle, or outright violence—is also framed as something outside the realm of strategic rebellion. Marlow and his fellow Europeans interpret native resistance not as a response to exploitation but as an expression of primal chaos. The natives do not resist in a way that is understood within European political discourse; instead, they are depicted as unknowable, acting on impulses wrapped with irrationality.

In all three works, native resistance is reduced to something pre-political (not apolitical), a mere feature of their existence rather than a calculated, rational rejection of foreign rule.

Another striking parallel between these three works is how the environment itself is used as an extension of the people who inhabit it, reinforcing colonial notions of the native as wild, untamed, and inherently different from the European. In Warriors, Hanley describes Somalia as a land of stark, wastes, merciless beauty—harsh and indifferent, much like its people. His descriptions of the desert mirror the traits he ascribes to the Somali warriors: unforgiving, resilient, and beyond the reach of foreign control. In The Tempest, the island functions as an enchanted, unknowable space, shaped by Prospero’s magic but still resistant to total mastery. Caliban, as the island’s original inhabitant, is described in terms that make him indistinguishable from the land itself—“freckled whelp,” “mooncalf”—suggesting that he, like the wilderness, exists outside European civilization.

In Heart of Darkness, the African jungle looms large as a metaphor for the “savage” world; it is dark, impenetrable, and ever-threatening, just like the native people are portrayed as unknowable and menacing. The deeper Marlow ventures into the jungle, the more he feels he is leaving the world of reason and entering a space governed by instincts, much the same way Hanley describes the Somali landscape as a place far from ‘our’ civilization, shaping the psyche of its inhabitants.

It is staggering how these works reflect each other not only in prose but also in plot, characters, and the narrative they try to convey. To further illustrate, dear reader, the protagonists of these three works feature Europeans who function both as observers and reluctant participants in the colonial world.

Hanley, despite his deep admiration for Somali resilience, cannot escape his role as an outsider. His observations are shaped by the contradictions of imperial thought; he respects the people, but his worldview remains structured by the colonial logic that renders them inscrutable. Prospero, though he has lived on the island for years, remains apart from it, seeking to impose order while never fully integrating. His treatment of Caliban—educating him, then enslaving him—mirrors the colonial paternalism found in Hanley’s reflections.

Marlow, as the narrator of Heart of Darkness, occupies a liminal position. He is neither fully aligned with the brutal imperialists nor free from the prejudices of his time. His fascination with Kurtz reflects the underlying tension in all three works: the colonizer’s simultaneous attraction to and repulsion from the people he seeks to rule.

And it is for this reason the celebrated Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe said that though Joseph Conrad brilliantly critiques colonialism, he cannot be read as a classic because of his dehumanizing portrayal of natives.

Related post